The importance of coaches, outside of athletic endeavors, was first brought to my attention by someone discussing the article Personal Best by Atul Gawande in the October 2011 issue of The New Yorker’s Annals of Medicine. And it makes sense, right? Athletes, singers, performers of all kinds, have coaches monitoring their every move and providing feedback to further fine tune their behaviors, so why shouldn’t this also be a useful tool in the work place, or even in your interpersonal life?

The trap many people fall into is that they are under the impression that they are able to adequately assess their own actions. They are the ones who know themselves the beset, after all. But, the issue here is that our perceptions are not objective, they are distorted by many things, and in the case of athletics, our sense of proprioception is never going to as good as another set of skilled, watchful eyes.

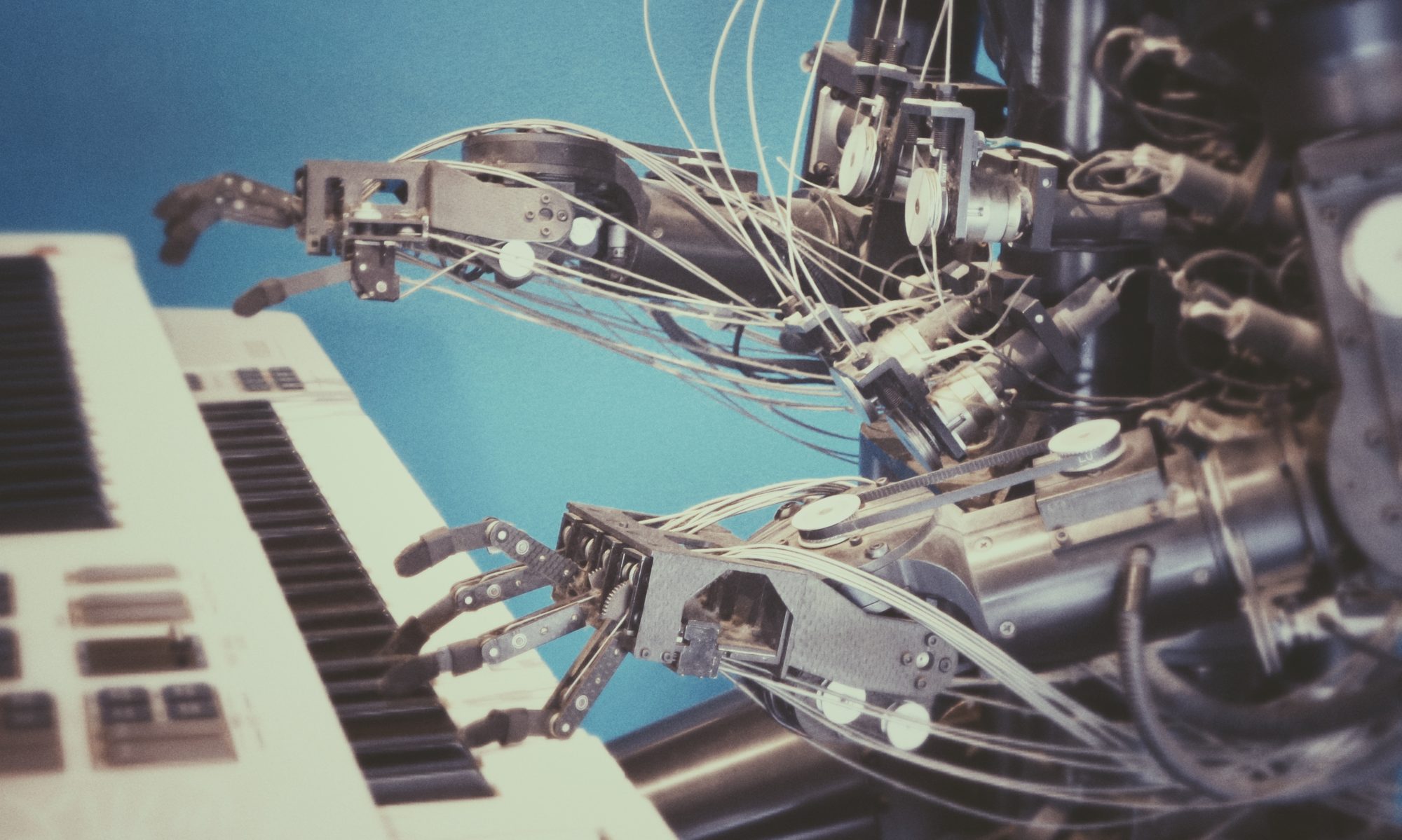

Take for example my more recent foray into superbike racing. I’ve been riding motorcycles nearly all my life, and finally took the leap to begin road racing. As anyone who has ever watched roadracing knows, the coolest thing you can do is drag knee through a corner. I mean, look at how awesome Marc Marquez looks doing this:

Now, when I started my coaching sessions, I knew I was so close to dragging knee… Until I got my coaches feedback and they showed me pictures of myself.

What the hell, I thought. I knew I was so close to dragging body parts on the race track. I could tell I was hanging off the bike so far, I was going so fast. Well, my perception of what was actually happening was far from the objective truth of it. And this is where some people have a very difficult time with things. They come into a situation and fall into one of the biggest traps someone can fall into, regardless of if they’re new or an elite level athlete: they aren’t coachable. They think their perception of reality is the objective truth of it. They think the feedback they are getting is wrong.

Now, for the sake of saving face, I listened to my coaches and got there. I mean, look at how cool I look.

Why This Matters Beyond Athletics

Ultimately, coaching helps to strengthen our self-awareness, emotional or otherwise. We may think we are doing something, whether it’s cornering effectively in motorcycle road racing, or responding adequately to an emotionally charged or difficult conversation in the workplace, but if we are only relying on our own perception of it, we are probably pretty far from the objective truth of the matter.

If we proceed day in and day out by assuming that our interpretations of things are correct,without ever checking that assumption, we will continue to reinforce behaviors based on these perceptions (or inputs). But what if these are wrong? Well, we will begin developing behaviors that are at best much less effective than they could be, and at worst completely inappropriate to the situation.

In Personal Best, Atul Gawande talks about how this has related to his performance as a surgeon. In his earlier years he improved every year, ultimately performing much better than national averages. That is, until one day he plateaued. Gawande recalls being at a medical conference and searching for an impromptu tennis match, having been a very competitive player in high school that took particular prided his serve. During the match, the other player, who played in college, mentioned “you know, you could get more power from your serve.”

He realized that what he thought he was doing, was not in fact what he was actually doing. He gradually realized his legs weren’t really underneath him when we swung his racket up into the air. His right leg dragged a few inches behind his body. With these realizations, and a bit of practice, his serve was drastically improved.

What Is a Coach, Anyway?

The concept of a coach is somewhat difficult to define. They teach, but they are not teachers. They can be bossy, but they’re not really your boss. In fact, they don’t even have to be good at what they’re coaching, they just have to be knowledgeable about it. Coaches simply observe, make a judgement about what they see based on their knowledge of the subject, and then guide.

As Gawande mentions, the coaching model is distinct from the traditional concept of pedagogy; in the latter there’s a presumption that the student will no longer need instruction. You get to a certain point and you’re done. You know everything there is to know. But how does this “being done” notion work in a world where things are always changing, techniques evolve, etc? In my mind, it fails many people.

The model for coaching, as opposed to pedagogy, is different in that it considers the latter naive about our human capacity for self-perfection. It firmly states that no matter how well prepared someone may have been at one point in time, nearly no one can actually maintain their best performance on their own.

Utilizing a Coach

Gawande inquires about the lack of coaching in classical performing arts with Julliard graduate and violin virtuoso Itzhak Perlman only to find out that, in a sense, he actually had a coach. Gawande asked “Why concert violinists didn’t have coaches, the way top athletes did. He (Perlman) said that he didn’t know but that it had always seemed a mistake to him. He had enjoyed the services of a coach all along.” Perlman indicated that he felt incredibly lucky to have met his wife, who was also a concert-level violinist, whom he’d relied on for feedback for the last 40 years. According to Perlman, “The great challenge in performing is listening to yourself. Your physicality, the sensation that you have as you play the violin, interferes with your accuracy of listening. What violinists perceive is often quite different from what audiences perceive. My wife always says that I don’t really know how I play. She is an extra ear… She is very tough, and that’s what I like about it.” Perlman’s wife, all along, had been next to him telling him if a passage was too fast, or too tight, or too mechanical, or any other myriad things that needed fixing.

California researchers in the early 80’s conducted a five year study of teacher-skill development in schools and noticed that when teachers only attended workshops new skill adoption rates were approximately ten percent, but when coaching was introduced, adoption rates passed 90 percent.

Good coaches know how to dissect a performance into its constituent components. They remove little items from the complex behaviors, bring them to the forefront to be thought about, practiced, and then insert them back in to the complex behavior. In sports, coaches focus on mechanics, conditioning, and strategy. In professional settings, and in particular in the classroom as Gawande illustrates, coaches do the same thing, but often focus on behaviors, attention span, and rates of learning.

Gawande decided to try to incorporate this concept of a coach into his operating room. He asked an accomplished surgeon to monitor him during one of his operations, one that he said couldn’t have gone better. Upon meeting with his coach afterward, who observed the entire operation, he was given many, albeit very minor, changes to incorporate. He was told to leave more room to the left which would have allowed the medical student to hold the retractor and free up the surgical assistant’s left hand. He was told to pay more attention to his elbows. He was told to think more about the positioning of the patient in comparison to everyone else, not just him. He was told a few times that he would have been more efficient, and therefore less tired, had he chosen a different instrument a couple of times, or changed his body positioning. Gawande stated “That one twenty minute discussion gave me more to consider and work on than I’d had in the past five years.”

When it comes down to it, all a coach does is monitor your inputs and outputs to a system, and provides a feedback mechanism to optimize the outputs. This often times means changing inputs, whether it’s the mechanics you’re using as an athlete, a particular teaching strategy you use as an instructor, or the manner in which you provide feedback to direct reports as a manager.

An Engineering Systems Example

Think about it like this: if the speedometer on your car is off by 20%, the speed you go when you set your cruise control will be wrong, even if you, and the car, both think it’s correct. Ultimately though, what you and your car think doesn’t matter as much as the objective reality of the situation when you get a speeding ticket. In this scenario the system is your car, including the cruise control, the input is your desired speed, and the output is the actual speed. The feedback by which the car is able to achieve this output speed is from some variety of wheel speed sensor or calibrated tachometer. The police officer is the coach.

In my motorcycle example above, the system is me and my motorcycle, the input is the lean angle and body position I want, and the output is the lean angle and body position that I’m achieving. My feedback mechanism is my internal proprioception. The coach is, well, my coach.

Some Final Thoughts

Coaching outside of athletics has become a bit of a fad over the last handful of years, but beware that bad coaching will make people worse. Coaches should foster an effective solution or change, not merely have you replicate a technique that they like. They should help you find what works for you, given that you and your situation are not just an exact duplicate of another thing like machines are.